How to Best Restore Historic Windows

Note: This blog is transcribed from Brent Hull's webinar, Repairing Historic Wooden Windows: What Architects Need to Know, hosted by the Traditional Building Conference.

How do you restore historic windows from the 1890s? Do you repair or do you build new? To begin, you’ll want to determine if it’s repairable and what parts need to be repaired. You’ll also want to assess the quality of the wood. Will it last?

Balance Sustainability, Energy Efficiency and Historic Integrity

Saving old windows is good for the environment. It conserves embodied energy and avoids overcrowding landfills. It also preserves old-growth wood which will last longer than the materials that new windows are made of. Saving the original windows preserves the historic integrity of the building.

What Style is This?

Windows define the architectural period and style of a

traditional building. For instance, the 2.5’ wide by 6’ tall window is from the

Victorian period 1850-1890. The windows shown above are in a house whose

architectural style is called “Italianate.”. A 3’ by 5.5’ or 3’ by 6’, window

is from the Arts and Crafts period 1880-1930. Windows tell a story.

Window glass can also help determine the age and period of a historic building.

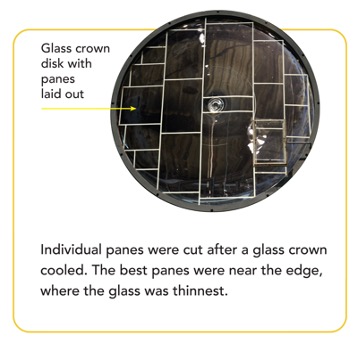

Crown or Table Glass (1700-1800)

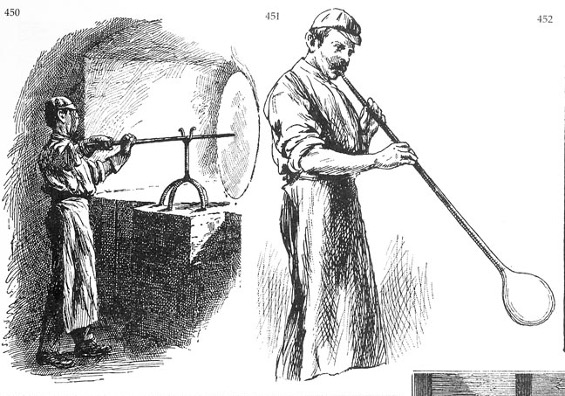

This kind of glass was made by taking a little bubble of glass at the end of a rod. Then the glassmaker would blow down his tube to expand that piece of molten glass. (Shown above right.) Then he would cut the end off and spin it. (Shown above middle.) The centrifugal force would expand that piece of glass. The glassmaker would keep it hot to expand it to 3’ or 3.5’ wide in diameter. Then after breaking it off the rod, the maker would create individual panes.

The size of the glass helps date it. In that 3’ diameter (Shown above left.) those different lines are broken up. There are only two large pieces with three medium-sized and then a few smaller ones. Historic buildings have small windowpanes because glassmakers did not yet have the technology to make large pane glass.

Crown or table glass is identified by the way the striations run through the glass. If there are “waves” or striations, you’ve got a pretty old piece of glass.

When you take the glass out of the sash during restoration, you’ll notice that one edge will be thicker than the other; and tapered. Because the glass was spun outward, the middle sections were much thicker than the outer sections of the glass pane.

Hand-blown Cylinder (1700-1800)

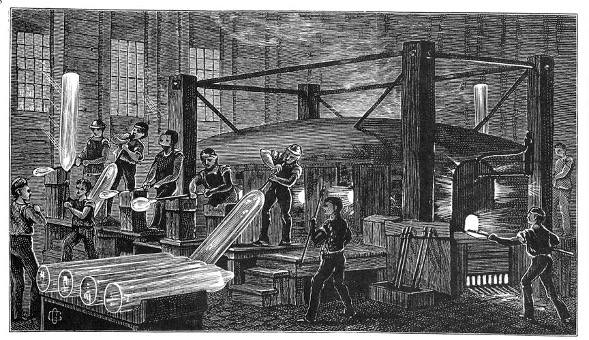

Later in this era, there was cylinder glass.

The process is similar to Crown glassmaking because the maker would blow

through a tube to make a piece into a large ball. But instead of cutting it and

spinning it, he would throw it down and slice it open, allowing the sides to

fall.

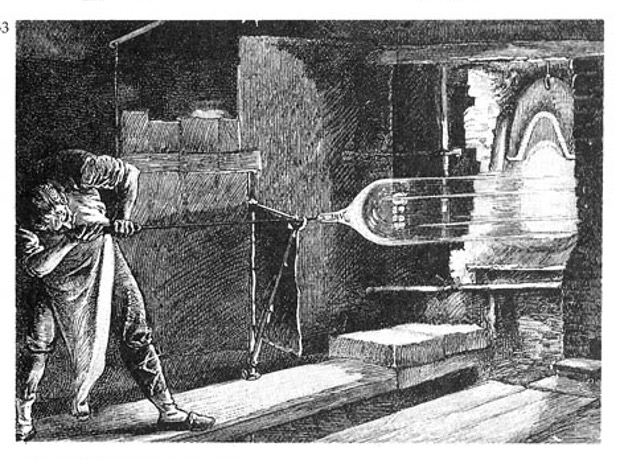

Shown above is a circular furnace for cylinder

glass creation. The workers are on platforms where they are blowing and

throwing the glass pieces. Once the tube was ready, they would cut it off the

tube and then cut a long line through it so the glass would roll out flat.

What is distinctive about this type glass is the striations and bubbles which are long and thin—not circular as you’d see in table glass. They’re long because they’ve been “thrown out.” This occurred in the early 1850s because industrial glass was not manufactured until after the Civil War.

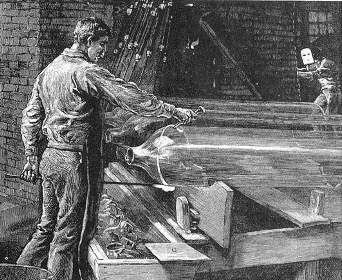

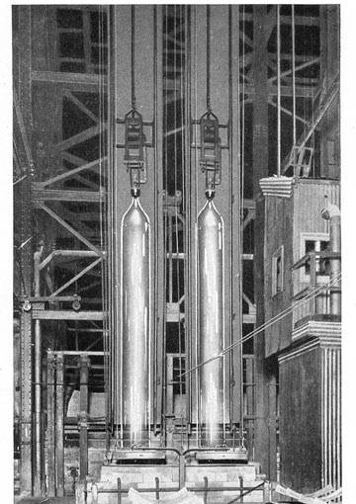

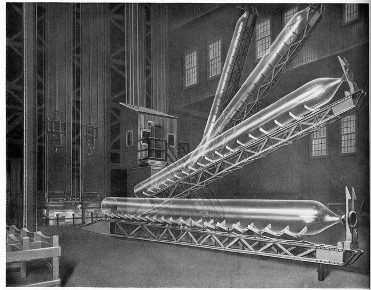

Machine

Cylinder Glass (1860-1930)

Machine cylinder glass was made until the 1930s. An arm drops down into a tube of molten glass, lifts it up and blows it at the same time to create long glass cylinders. Then they’re laid down, cut to length, and cut again down the middle to be laid out. This type of glass has a toffee consistency which is malleable.

Plate Glass (1860 – Present)

Plate glass is a post-industrial invention. Big wheels polished the sheets of glass.

Once the glass was ready it would be laid on a big table and graded. Many historic buildings have wavy glass. Glass can be dated and understood because of the way it was made.

Quality of Glass

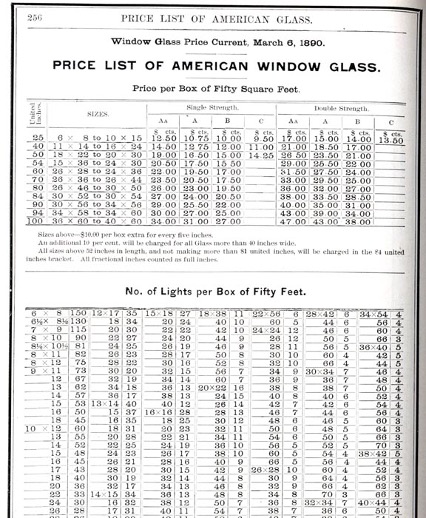

Above is an example of the glass A, B and C grading system for the single-strength and double-strength glass.

In the Colonial-era, windows were purchased by

glass pane size. Glass pane proportion, scale and detail mattered most.

Unlike later modern period windows which could

be horizontal in shape, early period windows were almost always vertically

oriented.

Tall, thin vertically oriented windows, 2’ or

2.5’ wide by 6’ or 7’ tall, were typical in Second Empire and Italianate buildings

of the mid to late 1800s. During this era, bigger was better. Muntin bars were

often painted black to make windows look like one pane of glass.

The Ranch Period

By1940, molten tin glass could be laid out in

continuous sheets on hot tin which allowed the glass to float across and dry

very easily. Because the glass slowly cooled there were no striations or

bubbles in it. Therefore, window glass made after 1940 does not have the

distinctive character of wavy lines. We can date the glass because of its size.

This is how picture windows started.

Old Wood Lasts Longer

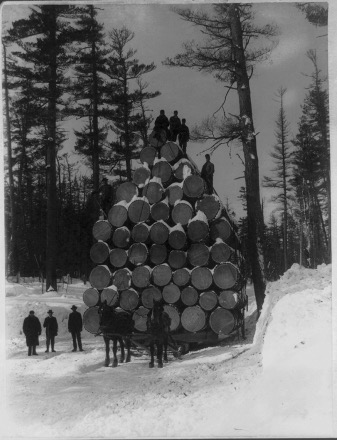

Old windows have character. The old-growth wood they’re made of has longevity.

Above is a 1940s logging photo from the Northwest, probably Washington State or Oregon, where large, virgin-growth redwood trees were harvested by lumbermen. There isn’t much of this wood left.

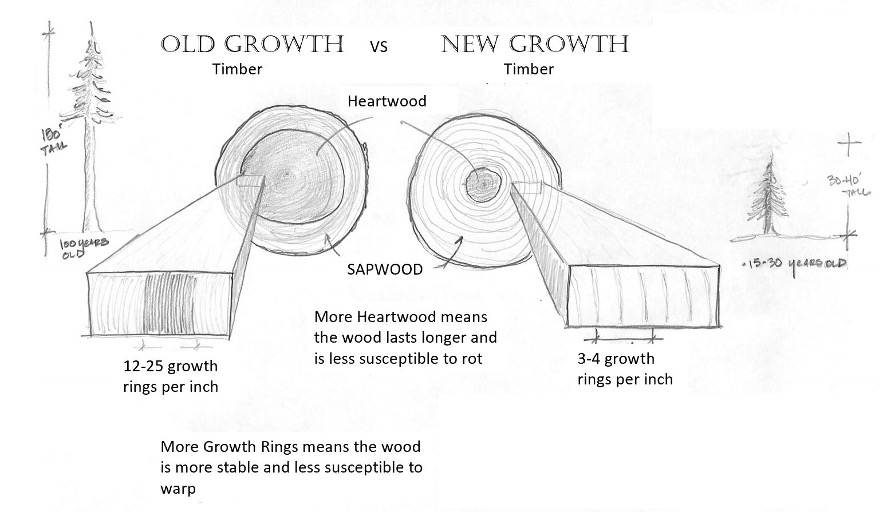

The Difference Between Old Wood and New Wood

There is quite a difference between old wood

and new wood. The middle photo above shows the quality of wood before and after

1940. The bottom piece of long-leaf pine wood shown has tight growth rings:

15-18 per inch. The new piece of wood has 3 or 5 rings per inch. The more

growth rings per inch the more durable the wood. The comparison is between how

wood grew historically versus the way wood grows now.

Above is an illustration of old growth wood. The tree is 180 ft. tall and over 200 years old. If you've ever been to a Redwood Forest, you know that it’s very dark under a canopy of branches. When a young tree grows under this shady canopy it gets very little sunlight. Therefore, the trunk of that tree will grow tall and thin, which means tighter growth rings. Due to the lack of sunlight, this tree will only grow branches at the very top. This tree grows very slowly with few branches on its trunk.

The tree on the right is a plantation grown

tree which gets sunlight in its early growth stage. It grows more branches

which creates more knots.

A tree’s growth occurs on the outer rim of the

trunk. This outer rim, right under the bark is called the cambium. This is

where the tree grows its layers. You can see the lines in these layers, called

cones, which move water up and down the tree trunk. In the middle of the tree

trunk, a darker color section is the heartwood.

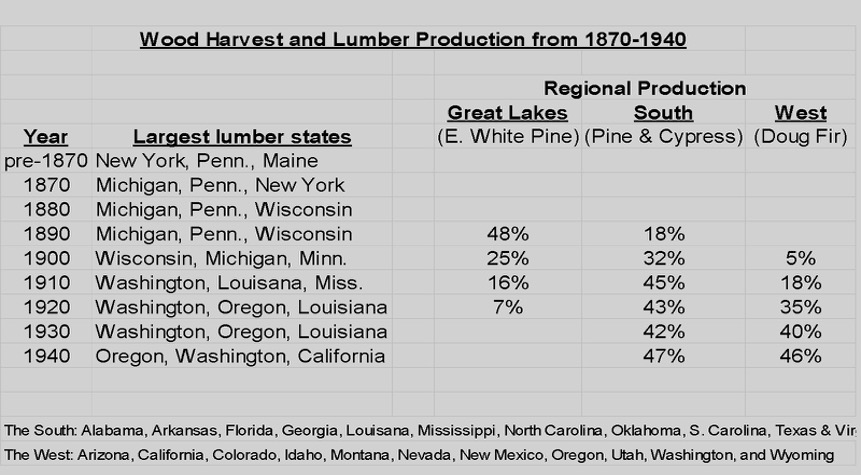

Lumber Harvesting Charts

There is a big difference between the heartwood on the new growth tree and the old growth tree. There’s significantly more heartwood on an old-growth tree. Softwood is the wood on the outside of the tree that is the fast-growing, does not hardened, won't last as long, and will rot faster. The new growth timber on the right has very little heartwood, or growth rings, because it grows so fast. Growth rings are the stability of the tree. Wood from a tree with fewer layers will twist and warp more. Wood from an old-growth tree trunk with lots of layers will be sturdier and rot resistant.

Lumber harvesting charts show where the wood comes from. Some regions of the country grow better wood than others, wood that is more distinctive. Hull Millwork restored a 1880s courthouse which had white pine doors, longleaf pine casings and windows. When this courthouse was built in the 1880s, the white pine lumber was imported from St. Louis. There was no white pine in Texas used for interiors. Each region has its own local variety of wood species.

Eastern white pine came from New York, Pennsylvania, Maine and Wisconsin. Eastern white pine lumber was cut in the winter, hauled by horse and wagon to the nearest river when, in the Springtime, it was floated to its destination. By 1890, with the advent of the railroad, lumber was shipped by rail car, especially lumber from the southern U.S. where rivers were flat and slow moving.

Prior to 1940, there was no Douglas Fir in Texas. So, you don’t find it in the historic buildings in this state.

Most of the wood used pre-1940 in Texas was longleaf pine and cypress. The wood species in historic buildings helps

us date these buildings.

By the end of 1940 most of the trees in virgin

forest had been cut down. There are still some very small virgin forests spread

out over the U.S., but most trees today are second growth or plantation grown

trees. Most of the wood used in new replacement windows today is Radiata

pine from the Western US, Chile and New Zealand. It is fast growing, less

durable and has lots of knots.

The

quality of the old growth lumber used in old windows is probably the best

reason to restore them.

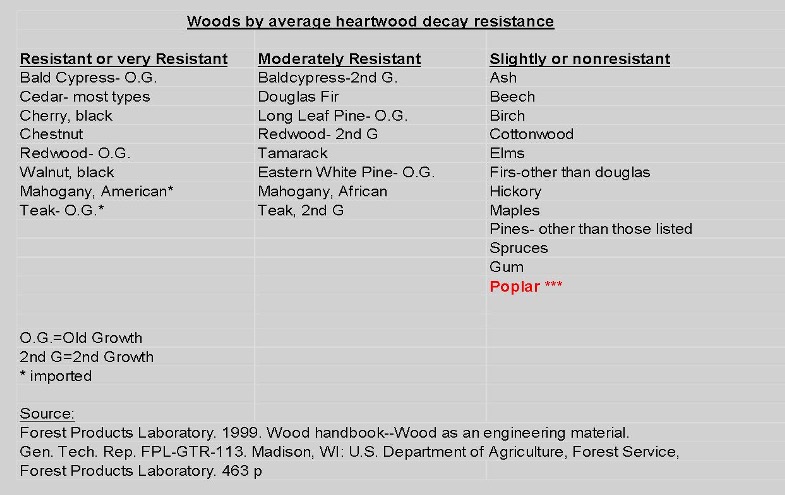

Information from the Forest Products Laboratory

shows the types of wood which are most resistant to rot, warping and decay. Hardwoods

like Bald Cypress and Cedar are very resistant to decay. Douglass Fir and Long leaf

Pine are moderately resistant. Pine wood species is not so resistant. New wood

rots faster when it is finger-jointed and not of good- wood quality. Its true

that “they don’t make wood like they used to.” But it is also true that the

right wood should be used in the right location.

When

specifying the right wood follow these rules:

- Keep wood in its natural

habitat - At least 10-15 growth rings per

inch - Old growth vs. new growth

Best woods:

- Longleaf pine (no others)

- Tidewater red cypress (not

yellow) - Fir-quarter-sawn

- Sapele-Mahogany-Spanish Cedar

Most of the cost in a new window is the labor

NOT the materials. Radiata pine cost $2

per board foot whereas Long leaf pine (old-growth wood) costs $6 per board

foot. Wood is only 20% the cost of the window so investing in the right quality

wood makes sense, for quality, durability, longevity and value. Hull Millwork

uses Long leaf pine, the best wood to use in our home state of Texas.

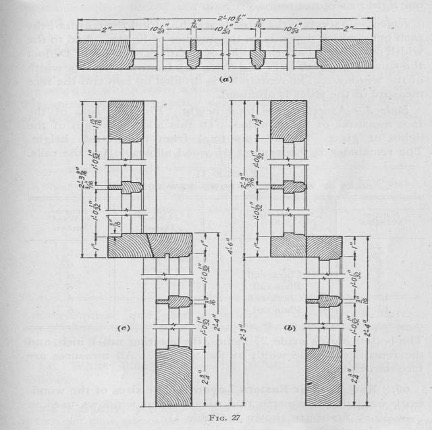

Design Consistency

Industrialization, and therefore manufacturing standardization, started in the 1860s and lasted through the 1930s. There was a 70-year period where windows were all made the same. The styles and rails, check rails and muntins are almost always the same. There are some styles and profiles of muntins that can change, but typically the bottom rail was 3”, the side rails were 2”, the check rails were 1.5”. These windows are quite easily repaired. Don’t remake the whole sash, just remake some of the window parts which costs less and lasts longer.

These window parts are easy to reproduce and

inexpensive. Using quality wood is the most important thing

Window

Restoration / Repair Process

- Abate

- Remove

- Strip

- Repair

- Re-Glaze

- Paint

- Install

Abate the area if you need to. Remove the windows and strip them in the shop. Repair them, reset the glass, re-glaze, paint and install them. It’s a consistent process with predictable costs.

Historic Window Restoration

At Hull Millwork we specialize in residential and commercial window restoration work. View our gallery of window restoration projects or contact us today about your next project.